Searches Aren’t Seizures: A Fourth Amendment Mix-Up

Keep searches and seizures conceptually distinct, and you are less likely to make the slip-up I witnessed at a recent federal appellate oral argument.

I recently listened to a federal appellate oral argument where an advocate blurred Fourth Amendment search doctrine into property-seizure doctrine. When the bench pushed back, he doubled down. The Fourth Amendment, he argued, is about “government overreach,” so the analyses should run together. The panel corrected him quickly. And the correction matters: searches and seizures protect different interests and require different tests.

The Fourth Amendment does not prohibit “overreach” in the abstract. Its first clause prohibits unreasonable searches and seizures, and that protection is not triggered until a search or seizure has occurred. So, the threshold question is: What counts as a “search” or “seizure”? Not everything you might expect.

A search under the Fourth Amendment occurs only when the government either (a) invades a person’s legitimate privacy expectations (think Katz) or (b) physically intrudes on a protected area to obtain information (think Jones’s trespass theory). Katz v. United States, 389 U.S. 347 (1967); United States v. Jones, 565 U.S. 400 (2012). Thus, while a police officer rummaging through a trash bin at the curb may look like a search, that sort of dumpster diving fails to trigger Fourth Amendment protections because garbage left out for collection—vulnerable to raccoons and nosy neighbors alike—carries no reasonable expectation of privacy. California v. Greenwood, 486 U.S. 35 (1988).

But a seizure of property is different. As to seizures, the Fourth Amendment protects against meaningful interference with your ability to use, control, or access your property (in short, your “possessory interests”). Segura v. United States, 468 U.S. 796 (1984). And critically, a seizure can occur even when no privacy interest is invaded and no information is sought. Soldal v. Cook County, 506 U.S. 56 (1992).

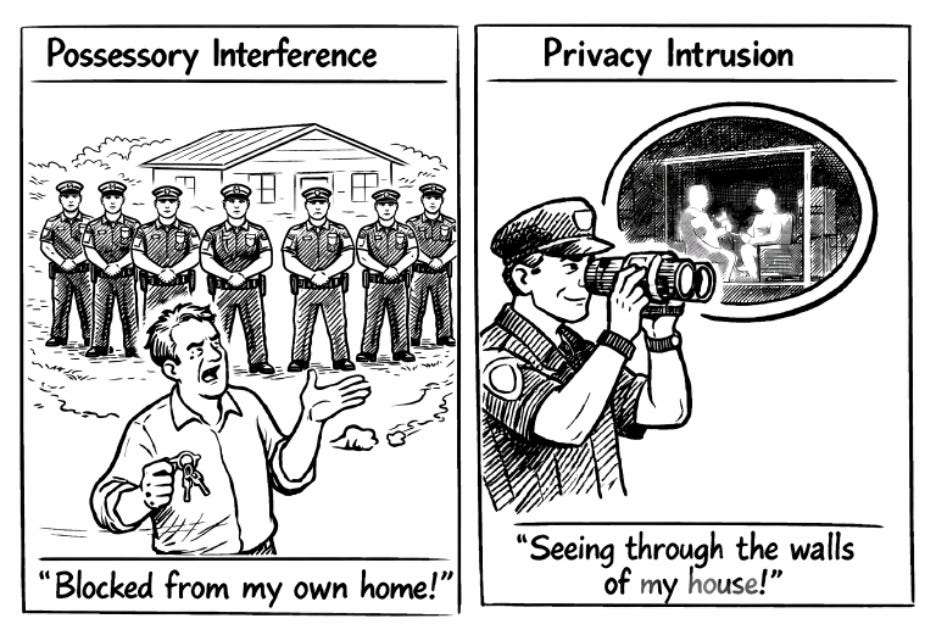

So, if the police are outside a home, has the home been seized, searched, both, or neither? The answer depends on what the police are doing and why.

If an officer blocks you from entering your own home, then they have interfered with your ability to access your home. Your home has been seized. Segura, 468 U.S. at 811.

But if that same officer instead uses a sense-enhancing tool (like a thermal imaging camera) to learn about private activities inside your home, then your expectation of privacy within your home has been trampled upon. Your home has been searched. Kyllo v. United States, 533 U.S. 27 (2001).

Finally, it is easy to see why advocates blur the categories: the Court itself sometimes uses “search and seizure” in a single breath. In Katz, for example, the Court described “electronically listening to and recording” a phone call as a “search and seizure.” 389 U.S. at 353.

For Fourth Amendment hygiene, it is cleaner to separate the interests being invaded. Eavesdropping is a privacy problem that implicates search jurisprudence, while tape-recording the same conversation is arguably a seizure. Keep searches and seizures conceptually distinct, and you are less likely to make the slip-up I witnessed.